I work with someone who asks me a LOT of questions about genealogy – how do I figure out this or that, how do I know how closely DNA matches are connected, and where do I find answers to particular questions? So I thought it might be a good time for a good old-fashioned “how to” post on the first steps to take if you would like to research your genealogy.

Here’s a little caveat: Genealogy is not just addictive, but contagious. The two questions people ask me most often are “Will you help me find…?” and “How do I start working on my own genealogy?” Once you start, your friends and family might want to get in on the fun.

First, I will give you the most essential piece of advice: write it down. All of it. This applies to everything you will do and everything you will encounter. Write it down. One day, you might ask yourself, “Wait – where did I get the information that great-great-grandpa smoked imported stogies and worked as a stone mason?” By writing down the publication or conversation with a family member, you’ll have your source. For example, this particular tidbit comes from the family history my great-great-aunt Espezzia dictated in 1991 with two of her sisters, including my Nana (great-grandmother).

Step 1: Gather Information

Your initial step should be to write down everything you already know about your family. Who is related to whom? Do you know where and when your parents were born? What about your grandparents and great-grandparents? Do you know where and when they died or were married?

Write down every single bit of knowledge you have on your family, even if it’s a note such as “Aunt Mary said Great-Grandma ran a dry goods store.” Your Aunt Mary might not remember the name of the store and she might give you a vague location, saying, “It was in Boston or Cambridge or somewhere around there…” But write it down nonetheless.

Step 2: Talk to Your Family

The next thing I urge people to do when they come to me for advice about how to research their family tree, is talk to family members. Begin visiting with or contacting those family members you are closest to, and start asking them questions. Keep in mind that parents or grandparents can forget things sometimes, which leaves us with more questions than answers. But that’s all right! Treat every tidbit of information as a clue. For now, you are gathering all the information you can. Verifying and building on it will come later.

In particular, I encourage you to speak to your parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, great-aunts, great-uncles, and cousins, especially older cousins in the same generations as your parents and grandparents. Don’t leave out anyone, unless you think they might treat your queries with hostility. I know my Nana’s (grandmother’s; yes, we call both of them Nana) first cousins have shared some very interesting information that my Nana or others did not recall, or share with me.

These older generations are precious. You may learn everything you need to know from one person, or you might get conflicting information from a few people that can help you narrow down some of your questions. I’ve had plenty of people come to me with family information that was incorrect, and that’s perfectly fine! The point of compiling this initial information is to confirm it, if possible.

To this day, I am most grateful to my great-great aunt, Espezzia, who took the time to share her story on tape and paper. The document everyone in our family now has is full of recollections by my great-grandmother and two of her sisters of their parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, and uncles, and their lives during their childhood. The sisters who worked on the family history were all nearly 90-years-old at the time, and the document itself is invaluable to their descendants.

Why did they do this? Had someone thought to ask Espezzia, her sisters, and brothers about their childhoods or their parents’ lives in Italy? I don’t know, but I’m so glad these women took the initiative to put their thoughts on paper for future generations.

Likewise, I’ve “interviewed” my Nana, my grandfather, my grandmother, cousins of theirs, my second cousins, an aunt, and my father. Genealogy is not just about adding names, dates, and places to a family tree. It’s akin to stepping back in time and putting yourself in your ancestors’ shoes. Talk to the older generations in your family now – don’t let the chance pass you by!

Step 3: Organizing the Information

Now that you’ve written down what you know about your family, and what they know, and what the people they know know… You get the idea. You should now have pages of notes. Perhaps it’s a single piece of lined paper with incomplete names and dates, and guesses as to places. Or maybe you have a smattering of emails from different relatives.

Paper genealogy is still where I feel most comfortable when it comes to collecting and organizing information. It makes life simpler to pull out a binder of charts or vital records for an “at a glance” look at things. Never underestimate the power of the basics. Most of us start out with these. I don’t know if any genealogists ever really phase them out of their work, even with all that family history software can do for us!

Now you need forms to organize your information into easy to read formats. You can Google the following forms and find PDF templates. I’m partial to the free forms available from Family Tree Magazine’s website at www.FamilyTreeMagazine.com. You are looking for the following forms:

- Five-Generation Ancestor Chart aka Pedigree Chart

- Family Group Sheet

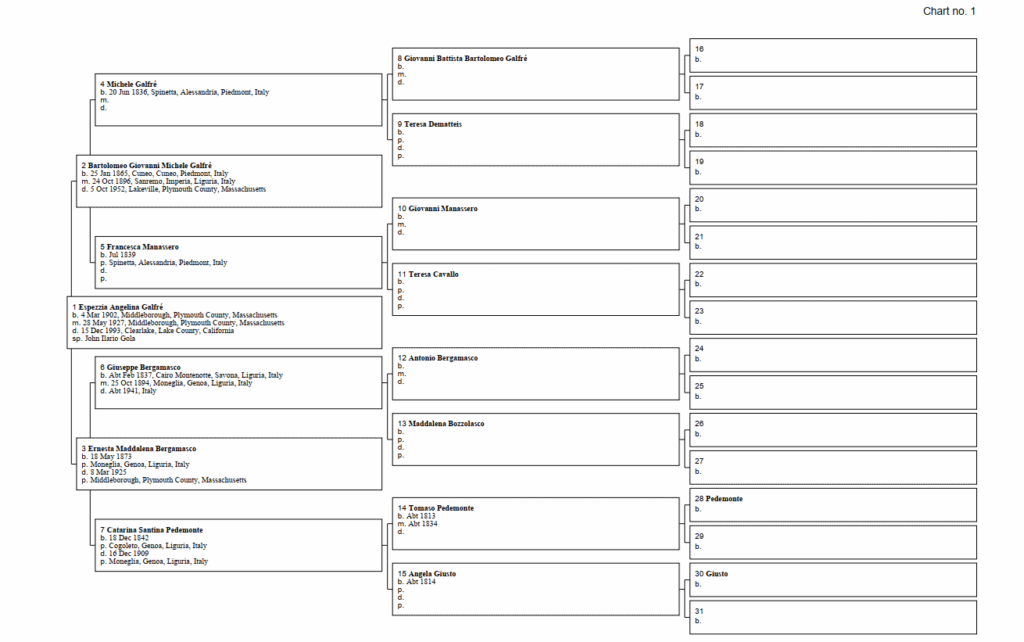

The five-generation ancestor chart is your most basic form and probably similar to what you might envision when you think of what a family tree looks like. It lays out your ancestors starting with you as number one. Use yourself as the starting point on chart number one by filling in your name on the very first line on the chart. Your parents will be next, and then their parents, and so forth. The standard practice is to list the men on the top line and the women on the line below them.

These charts allow you to go back a few generations, recording names and dates and places of birth, marriage, and death. It doesn’t go in depth about the people’s lives. Instead, it gives an overview of yourself or the ancestor listed on the first line, parents, grandparents, and so on.

This chart will give you an at-a-glance view of your ancestry and make it easy to see the areas where more information is needed. I recommend filling in any uncertain information with pencil first. You can always erase it and use pen later when you confirm a name, date, or place.

When you get to the fifth generation, it’s time to begin a new chart starting with the last people on those sixteen lines on the right side of the page. You will assign each of those people a chart number, and then begin a new chart, i.e. chart 2 will start with person 17 on chart 1, chart 3 will start with person 18 on chart 1, and so on. Your chart will look something like this:

Don’t worry if there are blanks in the chart. The point of genealogy is to fill those blanks and learn more about these people who – at this point – are probably just names and numbers to you. Soon you will know that Great-Grandpa Benjamin wasn’t just some man born January 1, 1900 in Dayton, Ohio. If you play your cards right, you’ll also learn he was a shoemaker with a penchant for wearing the same overalls every day and smoking a pipe, which his second wife absolutely despised but put up with anyway because she loved him so much.

You’ll notice, however, there’s no room to add such commentary to the five-generation ancestor chart. In fact, this form is only meant for direct ancestors, not collateral relatives. So it’s time to make use of the Family Group Sheet.

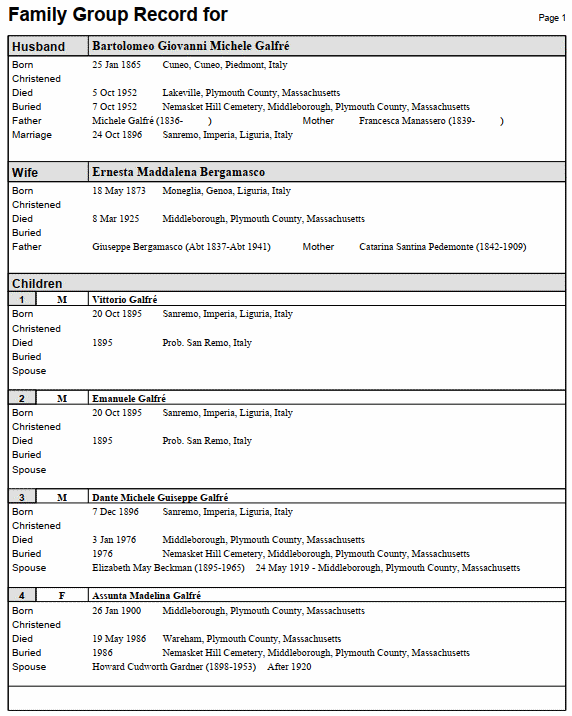

As you will see, this form has room to record much more information. Specifically, this allows you to write the names of a couple, their dates of life events (birth, marriage, and death), the names of their parents, and the names and life events of the couples’ children. Once completed, you will end up with something like this:

This form allows you to expand on the information about a particular couple and their children, which is especially useful if you need to employ advanced research tactics such as sideways searching aka “the FAN Club” (something I will try to post about one of these days).

A couple other forms you may want to have on hand are:

- Correspondence Log – handy for tracking emails and letters you write in your search for information.

- Research Worksheet or Journal – useful for tracking the sources you’ve already checked for a specific ancestor

- Research Calendar – a good way to track the dates of visits you’ve made to various locations for your research

- Research Checklist – a comprehensive listing of resources that you can check off as you view them for a specific ancestor

These forms are also available at Family Tree Magazine’s website or via a Google search.

This is the first step to organizing your information and research efforts into a logical format. However, don’t throw out your initial notes, particularly if there were questionable names, dates, and places! Either save or scan your notes. If they are handwritten, you may choose to transcribe them and print a copy.

I will try to post about genealogy software available and digitizing all of this. But I suggest keeping everything you’ve gathered together in one place, even if you ultimately scan and digitize it in some way. You may find that everything fits in a large manila envelope or folder at this point if you’re just starting. Don’t worry – when it’s time to outgrow that initial storage, there are many different systems for organizing your information.

Step 4: The Fun Stuff – Research!

Armed with knowledge and ready to learn more, you click to open your internet browser, and type the word “genealogy” in a search engine. Various results pop up and you select the most popular of them all – a behemoth of a genealogy site you’ve seen advertising during episodes of “Who Do You Think You Are” that, for a price, will give you access to everything you could ever want – censuses, vital records, books, and more!

Hold it right there. Back away from the keyboard.

As eager as you are to begin your journey, let’s talk about genealogy as a big business. There are the sites that offer a complete history of your surname, along with a lovely coat of arms to display on your wall. I hope by now, most people have learned those sites are nothing but public information brokers, and won’t give you anything of value.

Then there are the sites that do offer legitimate information for a subscription. I’m here to say put the credit card down and take a look at these gems before paying big bucks for access to genealogical records:

- Family Search at www.FamilySearch.org

- Google at www.Google.com

These are the initial sites to which I refer new researchers because they’re free and offer a wealth of information. I also like to suggest going to the state or regional genealogical society pertinent to your family history (for me, it’s the New England Historic Genealogical Society) and seeing what they have available if you become a member.

That’s not to say you won’t get good value for your dollar with any of the subscription sites. However, you will find censuses, vital records, military records, immigration records, and more at FamilySearch. And, if you are so inclined, you can give back as a volunteer in the future by transcribing records for them.

Finally, a warning: don’t copy every family tree you see online. It’s tempting, sure, but treat those family trees as hints and then verify information before adding it to your own!

Of course, there is so much more to learn about genealogy. These are just simple first steps to get anyone started tracing their genealogy or learning about their family history. As you go forward from here, there are many different directions and layers to this endeavor, and a different path for everyone. 🙂